Abstract

Many students have low reading motivation. Based on (reading) motivation theories, several mechanisms are distinguished that can foster reading motivation. Our goal in this meta-analysis was to examine the effects of theory-driven reading motivation interventions in school on students’ reading motivation and reading comprehension as well as to test which mechanisms are particularly effective in fostering motivation and comprehension. We conducted a literature search in ten online databases and identified 39 relevant effect studies. Positive effects on affirming motivations (d = 0.38), extrinsic motivations (d = 0.42), combined motivations (d = 0.17), and reading comprehension (d = 0.27) were found. The effect on undermining motivations (d = −0.01) was not significant. In particular, interventions that aimed to trigger interest had positive effects on affirming motivations and reading comprehension. Furthermore, effects on affirming motivations were larger if the total duration of the intervention was longer and if the share of boys in the sample was higher. Interventions delivered by researchers had larger effects on reading comprehension than interventions delivered by teachers. Finally, effects on reading comprehension were larger for primary schoolers than for secondary schoolers and larger for typical readers than for struggling readers. Implications for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Substantial numbers of students have problems comprehending texts. They are not able to perform reading tasks at the level considered the minimum required to participate fully in society (OECD, 2019a) and experience difficulties in school, as understanding texts is needed to acquire knowledge in different content domains (Reschly, 2010; Snow, 2002). These problems are partly related to students’ reading motivation, which can be defined as “the drive to read resulting from a comprehensive set of an individual’s beliefs about, attitudes towards, and goals for reading” (Conradi et al., 2014, p. 154). Research shows that students who are motivated to read, read more often and have better reading comprehension ability (Mol & Bus, 2011; Schiefele et al., 2012; Toste et al., 2020). However, substantial numbers of students have low reading motivation levels and only read infrequently (Nippold et al., 2005; OECD, 2019b; Strommen & Mates, 2004). Therefore, it is argued that reading instruction should not only focus on skills instruction but also on the promotion of reading motivation (e.g., De Naeghel & Van Keer, 2013; Vaknin-Nusbaum et al., 2018). The first aim of the current meta-analysis was to investigate to what extent theory-driven reading motivation interventions in school can contribute to higher reading motivation and whether this is accompanied by an increase in reading comprehension. Our second aim was to get more insight into what are effective ways to foster reading motivation.

Effects of Reading Motivation Interventions: Previous Meta-analyses

So far, a few meta-analyses have been conducted in which the effects of reading motivation interventions have been synthesized and compared systematically. Guthrie et al. (2007) investigated the effects of Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) on reading comprehension and different motivational variables, such as intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy. In CORI, motivational support and strategy instruction are combined in a content domain (e.g., science). Mean effect sizes for motivation ranged from Cohen’s d = 0.12 to 1.20, with a median of 0.30. Mean effect sizes for reading comprehension were larger, ranging from Cohen’s d = 0.65 to 0.93. More recently, Unrau et al. (2018) and McBreen and Savage (2020) examined the outcomes of a broader array of motivational interventions. Unrau et al. (2018) tested effects on reading self-efficacy and found a weighted mean effect size of Hedge’s g = 0.33. McBreen and Savage (2020) established mean effect sizes of Hedge’s g = 0.30 on reading motivation and Hedge’s g = 0.20 on reading achievement.

These meta-analyses have a number of shortcomings. The reviews by Guthrie et al. (2007) and Unrau et al. (2018) have a limited scope, targeting either one specific intervention or one specific outcome measure, thereby possibly overlooking relevant results of other kinds of interventions or on other types of variables. The meta-analysis by McBreen and Savage (2020) is more comprehensive but has three other drawbacks. First, the authors have included interventions both with and without a theoretical basis, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions on the mechanisms that steer intervention effects. Second, their meta-analysis includes both targeted and broad interventions, the latter including programs that combine motivational and other types of support (i.e., skills instruction). Since they do not use this variable as a moderator, definite conclusions on the effects of motivational support cannot be drawn: positive outcomes might very well be the result of other elements of the intervention. Third, McBreen and Savage (2020) based their moderator analyses on one, undifferentiated reading motivation variable, covering such concepts as intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, value, and extrinsic motivation. However, not all forms of motivation are equally beneficial for reading outcomes.

The present meta-analysis aims to meet these shortcomings in four ways. First, we take a broad scope; that is, we analyze the effects of a range of motivational programs on a variety of motivational outcomes. Second, we limit ourselves to theory-based interventions. This allows us to test which theoretical mechanisms contribute to the promotion of reading motivation and comprehension, thereby providing better insights into the effective ingredients of motivational interventions (see “Motivational mechanisms” for further explanation). Third, we aim to draw conclusions on the added value of motivational interventions by testing whether effects differ between programs that combine motivational support with skills instruction and those that do not. Fourth and finally, we apply a more differentiated approach to the moderator analyses. We based our approach on an analysis of the extent to which different types of motivation are beneficial for reading development. Based on previous conceptualizations of reading motivation (Schiefele et al., 2012; Guthrie & Coddington, 2009), we categorized motivational outcomes as affirming (e.g., intrinsic motivation and reading self-efficacy), extrinsic (e.g., reading for competition and recognition), or undermining (e.g., avoidance goals and perceived difficulty of reading). Affirming motivations are found to be most favorable for students’ reading achievement, whereas undermining motivations are unfavorable (Guthrie & Coddington, 2009; Guthrie et al., 2013; Ho & Guthrie, 2013; Van Steensel et al., 2019). Extrinsic motivations have been found to have small, no, or even negative effects on reading achievement (Becker et al., 2010; Schaffner et al., 2013; Schiefele et al., 2012; Stutz et al., 2016).

Reading Motivation Theories

Motivation is a complex construct with multiple dimensions (Conradi et al., 2014; Murphy & Alexander, 2000; Schiefele et al., 2012; Wigfield, 1997). These dimensions are elaborated in various motivation theories, which are also applied in the field of reading motivation (Conradi et al., 2014; Cook & Artino, 2016; Guthrie & Wigfield, 1999; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2016; Wigfield, 1997). Influential motivation theories are self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000), expectancy-value theory (EVT; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), social cognitive theory (SCT; Bandura, 1986), interest theory (IT; Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Krapp, 2002), achievement goal theory (AGT; Ames, 1992; Pintrich, 2000), and attribution theory (AT; Weiner, 1985). An adjacent model that is relevant to the field of reading motivation research is the reading engagement model (REM; Guthrie et al., 2007). Table 1 provides an overview and description of these theories.

Motivational Mechanisms

Together, the theories described in Table 1 propose several mechanisms through which affirming motivations, in particular, can be fostered. Feelings of autonomy, relatedness, and competence are central to SDT, which posits that motivation becomes more internalized to the extent that these psychological needs are met (Niemic & Ryan, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Applied to reading, autonomy can for example be supported by offering students a choice of texts (Stefanou et al., 2004). Positive interactions about books and collaboration in the classroom can contribute to feelings of relatedness (Guthrie et al., 2004; Nolen, 2007). Feelings of competence can be fostered by matching texts to students’ reading levels, by teaching strategies that support text comprehension, or by providing supportive feedback (Bandura, 1997; Margolis & McCabe, 2003; Walker, 2003). The need for competence is also central to EVT and SCT, which assume that expectancies of success and self-efficacy, respectively, promote students’ motivation to engage in activities such as reading (Bandura, 1986; Cook & Artino, 2016; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2016; Wigfield, 1997; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

In IT, interest is considered a driving force in student motivation and learning (Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Krapp, 2002). Students’ interest could, for example, be triggered by the use of interesting texts (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Schiefele, 1999) or by making real-world connections (Guthrie et al., 2007). The concept of interest also resounds in the concept of intrinsic value in EVT (Cook & Artino, 2016; Schiefele et al., 2012; Wigfield, 1997).

Based on AGT, stimulating (mastery) goals for reading may have beneficial effects on students’ reading motivation (Ames, 1992; Elliot, 1999; Pintrich, 2000). Mastery goals can be stimulated by stressing individual development instead of making social comparisons (Ames, 1992) and by integrating reading activities in “thematic units” to build expertise (Guthrie et al., 2004).

According to AT, motivation could be fostered by changing students’ attributions for learning. For example, if teachers emphasize that effort leads to success in reading and that failure is not caused by a lack of ability, this is expected to lead to more favorable attributions (Toland & Boyle, 2008; Weiner, 1985).

In REM, motivational support and strategic instruction are combined. As REM is based on SDT, SCT, and AGT, the motivational mechanisms of these theories are central to REM (Guthrie et al., 2007). According to REM, motivation is fostered if students’ interest is triggered; feelings of autonomy, relatedness, and competence are supported; and mastery goals are pursued (Guthrie et al., 2004).

Interventions may also focus on stimulating extrinsic forms of reading motivation. EVT encompasses values that are more external to students: attainment value and utility value, which could be fostered by emphasizing why reading is relevant and how developing one’s reading skills may help to reach future goals (Guthrie & Klauda, 2014; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). According to SDT, extrinsic motivators, such as rewards, may be expected to contribute to extrinsic motivations (Ryan & Deci, 2000). However, given the outcomes of previous research (Becker et al., 2010; Schaffner et al., 2013; Schiefele et al., 2012; Stutz et al., 2016), we do not expect interventions that mainly target extrinsic forms of motivation to positively contribute to students’ reading development.

Other Possible Moderators of Intervention Effects

In addition to the effects of motivational mechanisms, we were interested in other variables that might moderate intervention effects. These variables can be categorized as intervention, sample, study, and measurement characteristics.

Regarding intervention characteristics, we were first of all interested in whether effects differed between programs that focused on motivation only and programs that combined motivational support with other types of support. As explained earlier, inherent to many programs is that they combine motivational support with skills instruction, which makes it difficult to infer whether effects are caused by investing in student motivation (McBreen & Savage, 2020). Comparing programs that also include skills instruction with those that do not can provide an indication of the unique contribution of motivational support: such a comparison enables to analyze whether effects are still present when skills instruction is left out of the equation.

In addition, we were interested in moderators such as text genre, program duration, and the provider of the intervention. Students’ reading motivation may vary across different text genres: several studies indicate that students are more motivated to read narrative texts than informational texts (Guthrie et al., 2007; Lepper et al., 2021; McGeown et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2018). It is thus interesting to examine whether focusing on a specific genre has consequences for intervention effects. Concerning the duration of the intervention, we focused both on the number of sessions and the total amount of time students were exposed to the intervention. Although it may be expected that interventions are more effective if the duration of the intervention is longer, no effect of length of treatment was found in the meta-analysis by Unrau et al. (2018), indicating that longer interventions were not necessarily more effective than shorter interventions. Regarding the provider of the intervention, programs delivered by researchers may be more effective than those by teachers, as the former might be better able to deliver the interventions as intended (Edmonds et al., 2009; Okkinga et al., 2018).

Particular subgroups—secondary schoolers, struggling readers, and boys—are at greater risk of having low reading motivation (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Gottfried et al., 2001; Jacobs et al., 2002; Logan & Johnston, 2009; McKenna et al., 1995; McKenna et al., 2012; Parson et al., 2018; Toste et al., 2020; Vaknin-Nusbaum et al., 2018). Therefore, we were interested in whether interventions were more effective for these groups of students: we tested whether intervention effects were moderated by sample characteristics such as educational stage (primary versus secondary education), reading level, and gender.

Furthermore, we were interested in study characteristics such as how students were assigned to experimental and control groups, whether control groups received any treatment, and implementation quality. These variables might have consequences for the validity of conclusions on intervention effects. For instance, if students are not randomly assigned to experimental and control groups, differences between the groups might be explained by factors other than the intervention (Lispey, 2003). If part of the intervention is also offered to the control group, differences between the experimental and control group may be less pronounced (Wilson & Lipsey, 2001).

We also tested the effects of two measurement characteristics: measurement type and whether instruments were developed within the context of the study. For measurement type, a distinction was made between self-reports, teacher-reports, observations, and tests. Instruments that were developed within the context of the study may be expected to be more closely related to the content of an intervention, and therefore yield larger effects than study-independent measures (McBreen & Savage, 2020; Wilson & Lipsey, 2001). Operationalizations of all moderators are described in the “Method” section.

Research Questions

The objectives of the current meta-analysis resulted in the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the effects of reading motivation interventions on reading motivation and reading comprehension?

-

2.

Which intervention, sample, study, and measurement characteristics moderate intervention effects?

Method

Literature Search and Selection Criteria

Eight electronic databases were searched: Embase (via embase.com), MEDLINE, and PsycINFO (via Ovid), Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC, and CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), and Cochrane Central (via Wiley). Additional references were retrieved from PubMed (the subset as supplied by the publisher, containing the most recent, nonindexed articles) and Google Scholar. The search strategies were designed by the researchers together with an experienced librarian. Three sets of terms were combined: terms for reading, for motivation, and for educational interventions or programs. All terms were thesaurus terms and words in the title and/or abstract. A broad filter for studies related to children (aged 6 to 18 years) was used. The search was limited to articles published in peer-reviewed journals, to increase the probability of including studies with high methodological quality. A full overview of the search strategies for all databases can be found in the “Supplementary Information.” In the initial search, which was carried out on 8 April 2019, 9326 titles were identified, of which 5723 remained after removing duplicates. An update of the search on 6 May 2022 resulted in 3803 additional titles, of which 2166 remained after removing duplicates. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (a) the effects of an intervention aimed at fostering reading motivation were analyzed, (b) the intervention was based on a (reading) motivation theory, (c) the intervention was conducted at school, (d) the study focused on children in the range from Grade 1 until the end of secondary school, (e) the study contained an experimental and control group, (f) the dependent variables included measures of reading motivation, and (g) the study provided effect sizes or information allowing the calculation of effect sizes (sample size, means, and SD’s, or results of statistical testing). Studies were excluded (a) if the paper was in another language than English, (b) if the focus of the intervention was on reading in a foreign language, and (c) if the study focused on specific target groups (e.g., children with learning, emotional, or behavioral disorders).

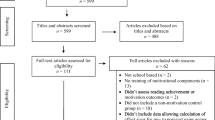

All results of the initial literature search were screened on title and abstract according to these criteria by the first and third authors. The results of the search update were screened by the first author and a graduate student. They screened and coded all titles independently. Full texts of possibly relevant studies were assessed on the same criteria to compile the final selection. If articles were not directly accessible, we tried to retrieve them by contacting the authors. For five possibly relevant articles, we were not able to retrieve the full text. If studies were eligible, but the statistical data reported were insufficient to be included in the meta-analysis, we e-mailed the authors to request the necessary information. In this way, we received additional data for four studies. This final stage of screening led to the inclusion of 33 studies in the initial search and six studies in the search update. Thus, 39 studies were included in the meta-analysis. We additionally consulted the reference lists of the meta-analyses by Guthrie et al. (2007) and McBreen and Savage (2020). However, this did not lead to the inclusion of any additional studies. All studies in these meta-analyses that met our inclusion criteria were already identified by our literature search. Interrater agreement for the selection of studies was 99.6%. Disagreements were discussed until an agreement was reached. For a schematic overview of the selection procedure, see the flow chart in Fig. 1.

Coding Procedure

All included studies were coded according to a scheme, which was developed and pilot-tested by the first and second authors. The scheme allowed the coding of bibliographic information, intervention characteristics, sample characteristics, study characteristics, and measurement characteristics. All studies of the initial search were double-coded by the first and third authors. Studies of the search update were double-coded by the first author and a graduate student. Interrater agreement was 90.3% (range: 80.4% to 100%). Interrater agreement was lowest for the number of sessions and the total duration of the intervention, often because the information provided by the primary studies was unclear. All disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached.

The following bibliographic information was recorded: title of the article, author name(s), and publication year. In the “Intervention Characteristics” section, the name of the intervention was registered and codes were given for its theoretical basis, the motivational mechanism(s) it tried to elicit, whether skills instruction was provided, the type of texts used in the intervention, the provider of the intervention, the number of sessions, and the total duration of the intervention. Interventions were only coded as based on a specific theory if the theory itself, key theorists, and/or key concepts of the theory were explicitly mentioned and linked to the content of the intervention. Regarding motivational mechanisms, we coded whether the intervention aimed to support autonomy, relatedness, or feelings of competence, trigger interest, stimulate mastery goals, change attributions, emphasize the value of reading, or whether it offered extrinsic motivators. Interventions were coded as providing skills instruction if motivational support was, for example, complemented by reading strategy instruction or fluency practice. Concerning text genre, we specified whether narrative texts, informational texts, or both were used. In some interventions, no texts but only sentences or words were used for reading. The assumption underlying such studies is that increased feelings of competence in word reading may also increase students’ motivation for reading texts (Toste, 2017, 2019). We also specified whether the intervention was delivered by researchers or not. Finally, the number of sessions and total duration of the intervention (the number of sessions multiplied by the duration of one session) were registered.

Samples were described according to the following variables: gender, educational stage, and reading level. We specified the percentage of boys in the sample, made a distinction between primary and secondary schoolers (as indicated in the original study), and we specified whether the sample consisted mainly of struggling readers. A sample was considered to consist mainly of struggling readers if the authors reported that at least 50% of the participants lagged in reading achievement (e.g., based on standardized test scores).

Concerning study characteristics, information was recorded on the design of the study, control group type, and implementation quality. We distinguished experiments and quasi-experiments. Studies were only coded as an experiment if randomization was applied at the individual level. If classes or schools were randomly assigned to the experimental and control condition, this was considered a quasi-experimental design. For all control groups, we specified whether they also received (part of) an intervention, which may have contributed to their reading motivation and/or reading comprehension. Furthermore, we registered information about implementation quality. However, many studies did not report on implementation quality (38.5%) or, if they did, the available information varied considerably. Therefore, we had to exclude this variable from the analyses.

Concerning measurement characteristics, we first coded whether the effect measures pertained to reading motivation or reading comprehension. We focused on reading comprehension as indicator of reading achievement, as gaining meaning and knowledge from a text can be considered the main purpose of reading (Snow, 2002). All motivation variables were further categorized as affirming, extrinsic, or undermining. Intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, mastery goals, perceived autonomy, social motivation, and intrinsic value of reading are considered (aspects of) affirming motivations (Guthrie & Coddington, 2009). Performance goals, reading for competition, and recognition were coded as extrinsic reading motivations (e.g., Guthrie & Coddington, 2009; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). Undermining motivations include constructs such as avoidance goals or reading anxiety (Guthrie & Coddington, 2009; Van Steensel et al., 2019). Some measures comprised indicators of more than one category (e.g., both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation), so a fourth category was added (combined motivations). Furthermore, we coded whether the post-test was immediately after the intervention or delayed, which type of measurement was used, and whether instruments were developed within the context of the study or study-independent measures (e.g., standardized tests) were used. Finally, we entered the statistical information necessary to compute effect sizes (mean, SD, and n, or, if unavailable, test statistics such as t or F) or the effect sizes (Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, or η2) provided by the authors.

Data Analysis

Because some studies included more than one experiment, experimental condition, or subsample, “experimental comparison” was used as the basis for the analyses. We first computed a weighted effect size for affirming motivations, extrinsic motivations, undermining motivations, combined motivations, and/or reading comprehension per experimental comparison (using the standardized mean difference: Cohen’s d), for which we used the available statistical information. Some studies included one instrument with several subscales; in such cases, we selected the overall scale. If a study included several indicators of reading motivation or reading comprehension, we aggregated the effect sizes per experimental comparison to prevent that the same experimental condition was included multiple times in the analyses and thus had a disproportionate contribution to the average effect.

If present, we used both pre-test and post-test data for computing effect sizes. In some studies, no means and SDs were provided. In these cases, we used the effect sizes provided by the authors or computed the effect sizes based on statistical data such as t values, F values, and p values, together with information on sample size.

We computed mean effect sizes for all outcome measures based on random-effects models, in which heterogeneity across studies is taken into account. To account for differences in sampling error related to sample size, random effects models weigh the mean effect size by the variance of the sample as well as by the variance between studies. To examine whether the variance in effect sizes between studies was related to intervention, sample, study, and measurement characteristics, we conducted moderator analyses based on categorical models analogous to ANOVA and with meta-regression in the case of continuous moderator variables. To test the between-group differences in the categorical random-effects analysis, we calculated the Q-statistic for between-group means. In the random-effects meta-regression models, we tested the significance of the individual regression coefficients with a Z-test.

Finally, we looked for indications of publication bias (Lipsey & Wilson, 1993). Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method (Duval & Tweedie, 2000) indicated that the effect size for affirming motivations of 0.38 [0.25;0.50] would change into 0.47 [0.34;0.60] after correction for publication bias with eight trimmed studies. The presence of publication bias was not confirmed by Egger’s linear regression test for asymmetry (intercept = 0.83; SE = 0.71; t(53) = 1.17, p = .25; Egger et al., 1997). For reading comprehension, Egger’s linear regression test for asymmetry indicated significant publication bias (intercept = 2.17, SE = 0.74, t(37) = 2.93, p = .01). Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method only revealed two trimmed studies. After correction for publication bias, the effect size would slightly change from 0.27 [0.17;0.37] to 0.30 [0.19;0.40]. Thus, weak indications for publication bias were found, but after correction for publication bias, effects would be larger instead of smaller. All analyses were performed by Author 4, using a registered copy of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis statistical software (version 3.0; Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

Results

Description of the Interventions

The 39 studies included in this meta-analysis encompass 40 interventions. An overview of all studies is provided in Appendix 1. Four programs were examined in more than one study. CORI was evaluated in four studies (studies 10, 11, 36, and 37). Learning Strategies Curriculum (Study 5 and 6), United States History for Engaged Reading (Study 29 and 30), and Multisyllabic Word Reading + Motivational Beliefs (Study 32 and 33) were evaluated twice. The remaining interventions were included once.

Most interventions were based on the reading engagement model (n = 11; 28%). The other interventions were based on self-determination theory (n = 6; 15%), interest theory (n = 4; 10%), expectancy-value theory (n = 3; 8%), attribution theory (n = 3; 8%), social cognitive theory (n = 3; 8%), and achievement goal theory (n = 2; 5%). Eight interventions (20%) were based on a combination of motivation theories, namely, AGT and SCT (n = 3; 8%), AGT and SDT (n = 2; 5%), IT and SDT (n = 1; 3%), IT and REM (n = 1; 3%), and REM and EVT (n = 1; 3%).

Regarding motivational mechanisms, most interventions aimed to trigger interest (n = 21; 53%), foster feelings of competence (n = 20; 50%), support relatedness (n = 14; 35%), stimulate mastery goals (n = 13; 33%), or support autonomy (n = 12; 30%). In a smaller number of interventions, motivation was fostered by changing attributions (n = 5; 13%), offering extrinsic motivators (n = 3; 8%), or emphasizing the value of reading (n = 1; 3%). Appendix 2 provides several examples of how these motivational mechanisms were applied in the interventions.

In approximately half of the interventions (n = 23; 58%), motivational support was complemented with skills instruction, such as teaching reading strategies or practicing fluent reading. In most interventions, narrative texts (n = 8; 20%), informational texts (n = 12; 30%), or both (n = 16; 40%) were used. In some interventions, only words or sentences were used for reading (n = 4; 10%). The interventions were delivered by either a researcher (n = 13; 33%) or someone else (n = 26; 65%), mostly teachers (n = 23) and in some cases preservice teachers (n = 1), volunteers (n = 1) or tutors with an undergraduate degree (n = 1). For one intervention, no information was provided about its provider. The total duration of the interventions varied strongly, ranging from less than half an hour to 195 h. Although some interventions consisted of only one session, other interventions were implemented two lessons a day for several months (maximum of 260 sessions).

Most interventions targeted primary school students (n = 32; 80%), whereas a much smaller number of interventions was directed at secondary school students (n = 8; 20%). Although most interventions focused on typical (i.e., heterogeneous groups of) readers (n = 25; 63%), a substantial number of the interventions targeted struggling readers (n = 15; 38%). The percentage of boys in the studies ranged from 35.42% to 75.00%.

Intervention Effects

To answer Research Question 1, we first analyzed the overall intervention effects on affirming reading motivations, extrinsic reading motivations, undermining reading motivations, combined motivations, and reading comprehension. The 39 studies in the meta-analysis included 55 experimental comparisons targeting affirming motivations, 12 targeting extrinsic motivations, eight targeting undermining motivations, five targeting combined motivations, and 39 targeting reading comprehension. The interventions had small, significant positive effects on affirming motivations (Cohen’s d = 0.38; SE = 0.06), extrinsic motivations (Cohen’s d = 0.42; SE = 0.16), and reading comprehension (Cohen’s d = 0.27; SE = 0.05), and a significant, but trivial effect on combined motivation scores (Cohen’s d = 0.17; SE = 0.04). The mean effect on undermining motivations was not significant (Cohen’s d = -0.01; SE = 0.07).

Subsequently, we compared effects on immediate and delayed post-tests. The time between the intervention and delayed post-test ranged from 2 to 28 weeks. Delayed post-test results were only reported for affirming motivations (k = 5), undermining motivations (k = 2), and reading comprehension (k = 7). For affirming motivations, a small effect was found on immediate post-tests (Cohen’s d = 0.40; SE = 0.07) and a trivial effect on delayed post-tests (Cohen’s d = 0.19; SE = 0.13). Effects on undermining motivations were neither significant on immediate post-tests (Cohen’s d = -0.07, SE = 0.08) nor delayed post-tests (Cohen’s d = -0.03, SE = 0.15). For reading comprehension, a small effect was found on immediate post-tests (Cohen’s d = 0.29; SE = 0.06) and a trivial effect on delayed post-tests (Cohen’s d = 0.16; SE = 0.07). Effects on immediate and delayed post-tests did not significantly differ for any of the outcomes (affirming motivations: Q(1) = 2.00, p = .16; undermining motivations: Q(1) = 0.05, p = .83; reading comprehension: Q(1) = 1.99, p = 0.16).

Moderator Analyses

To explain variability in effect sizes, we conducted moderator analyses based on intervention, sample, study, and measurement characteristics (Research Question 2). Moderator analyses were performed for immediate post-tests on affirming reading motivations and reading comprehension only, as few studies investigated effects on delayed post-tests and on extrinsic motivations, undermining motivations, and combined motivations. The outcomes of all moderator analyses are displayed in Table 2.

Intervention Characteristics

In the first series of moderator analyses, we analyzed the effects of intervention characteristics. Motivational mechanism was shown to influence program effects on reading motivation and reading comprehension. Interest was a significant positive moderator of affirming motivations and reading comprehension: interventions that triggered interest had larger effects on affirming motivations and reading comprehension than those that did not. No significant moderator effects were found for the other motivational mechanisms. We found no effect of the combination of motivation interventions with skills instruction: programs that focused solely on motivation were equally effective in stimulating affirming motivations and reading comprehension as programs that combined this with, for instance, reading strategy instruction. Furthermore, intervention effects were not moderated by the type of texts used in the interventions. Interventions using narrative texts, informational texts, or sentences/words for reading were equally effective in stimulating affirming motivations and reading comprehension. Provider of the intervention proved to be a significant moderator of reading comprehension, but not of affirming reading motivations: interventions delivered by researchers had larger effects on reading comprehension than interventions delivered by others. The effects of the number of sessions and total duration were analyzed using meta-regression analysis. The number of sessions was not related to effects on affirming motivations and reading comprehension. The effect of total duration was significant for affirming motivations but not for reading comprehension. Effects on affirming motivations were larger if the total duration of the intervention was longer.

Sample Characteristics

In the second series of moderator analyses, we examined the effects of sample characteristics. Educational stage was a significant moderator of effects on reading comprehension; interventions involving primary schoolers were more effective than interventions involving secondary schoolers. Interventions involving primary and secondary schoolers were equally effective in promoting affirming reading motivations. Reading level proved to be a significant moderator of reading comprehension, but not of affirming motivations. The interventions had significantly larger effects on reading comprehension if the sample included mainly typical readers than if it included mainly struggling readers. The effect of the percentage of boys was analyzed using meta-regression analysis. The outcome was significant for affirming reading motivations, but not for reading comprehension. Effects on affirming reading motivations were larger if the share of boys in the sample was higher.

Study Characteristics

In the third series of moderator analyses, we analyzed the effects of two study characteristics: study design and type of control group. The moderator analyses did not reveal any significant effects of these variables.

Measurement Characteristics

In the fourth and final series of moderator analyses, we examined the effects of measurement characteristics. A significant effect of measurement type was found on affirming motivations, indicating that effects were largest for teacher reports, as compared to self-reports and observations. However, it should be noted that teacher reports were used in only one study. Reading comprehension was measured by tests in all studies, so no moderator analyses of measurement type on reading comprehension were conducted. Finally, effects on measurements developed within the context of the study and study-independent measures did not significantly differ.

Discussion

The objectives of this meta-analysis were to investigate the effects of theory-based reading motivation interventions in school on reading motivation and reading comprehension (Research Question 1) and to examine whether effects were moderated by predefined intervention, sample, study, and measurement characteristics (Research Question 2). The results indicate that investing in reading motivation can positively affect students’ reading motivation and reading comprehension. Effects on reading motivation were moderated by the motivational mechanism elicited in the intervention, the duration of the intervention, gender, and type of measurement. Interventions that aimed to trigger interest had the largest effects on affirming motivations. Furthermore, effects were larger if the total duration of the intervention was longer and if the share of boys in the sample was higher. Finally, larger effects on affirming motivations were found on teacher reports, as compared to self-reports and observations. Effects on reading comprehension were moderated by the motivational mechanism elicited in the intervention, the provider of the intervention, educational stage, and reading level. Interventions that aimed to trigger interest had the largest effects on reading comprehension. Furthermore, interventions delivered by researchers had larger effects than interventions delivered by others (mostly teachers). Effects on reading comprehension were significantly larger for primary schoolers than for secondary schoolers. Finally, effects were significantly larger for typical readers than for struggling readers.

The positive effects we found on reading motivation and reading comprehension largely correspond to the results of earlier meta-analyses (Guthrie et al., 2007; McBreen & Savage, 2020; Unrau et al., 2018). Comparable to previous meta-analyses, the effects we found were mostly small but significant, although for some categories of studies average effects could range up to medium; for instance, we found a medium effect on affirming motivations of programs that trigger interest. Our outcomes thus give further support to the assumption that reading motivation can be fostered by educational interventions and that, by promoting reading motivation, students’ reading achievement can be increased. Apparently, increased motivation as an outcome of program participation results in students reading more frequently, which enables them to more effectively practice their reading comprehension skills. Students might then enter a process of reciprocal causation, where increased motivation and proficiency mutually influence each other, eventually leading to long-term benefits (Morgan & Fuchs, 2007; Stanovich, 1986). Our meta-analysis provides little ground for such long-term benefits, however: follow-up effects were significant, but trivial at best. Moreover, effects on delayed post-tests were included in a limited number of studies and the time between the intervention and delayed post-tests varied strongly. More research is thus needed to draw definite conclusions about long-term effects.

Effects on reading motivation appear to depend on the type of motivation. Significant positive effects were found on affirming and extrinsic motivations. Even though extrinsic motivations were hardly emphasized in the interventions, the effect on extrinsic motivations was as large as that on affirming motivations. This may be explained by previous observations of a positive relation between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: studies by Schaffner et al. (2013) and Troyer et al. (2019) found that students with higher intrinsic motivation often have higher extrinsic motivation as well. For intervention effects, this implies that an increase in intrinsic motivation may be paralleled by an increase in extrinsic motivation. Particularly in a school context, enhanced enjoyment of reading may, for instance, go hand in hand with an enhanced sense of its importance for students’ futures. The effect on undermining motivations was not significant, suggesting that current interventions are not sufficient to decrease undermining motivations. Undermining motivations are thought to be the consequence of an accumulation of negative reading experiences throughout students’ school careers and are thus likely to be persistent (Nielen et al., 2016). Guthrie et al. (2009) suggest that to decrease undermining motivations a strong structure of motivational support is necessary: a combination of various motivational mechanisms over an extended period of time may be needed to reduce undermining motivations. As only few studies examined effects on undermining motivations, additional research is needed to decide whether this assumption can be confirmed.

As we analyzed the effects of a range of reading motivation interventions, while at the same time limiting ourselves to theory-based interventions, the results provide new insights into which theory-driven motivational mechanisms are particularly effective. Moderator analyses suggest that interventions in which interest is triggered have the largest effect on affirming motivations and reading comprehension. This does not necessarily mean that other mechanisms (e.g., autonomy support or mastery goals) were ineffective. Since often multiple mechanisms were combined in one intervention, the moderator effect of interest signals that it matters whether interest is part of the package offered (for a similar interpretation, see Okkinga et al., 2018). Interest could thus be seen as one of the main determinants of a successful intervention. Providing students with reading materials that match their individual interests or devising reading activities that trigger situational interest might be seen as a precondition for motivation to arise.

Interventions with and without skills instruction were equally effective in improving reading motivation and reading comprehension. This outcome can be interpreted as indicative of the added value of motivational support for reading. The observation that motivation-only interventions yield similar effects as broad interventions do, suggests that positive intervention effects are not necessarily attributable to other elements of an intervention but can be pinpointed to motivational support. This makes our estimate of the effects of motivational support more precise than in, for instance, the previous meta-analysis by McBreen and Savage (2020). At the same time, it would be risky to conclude that motivational support alone is sufficient to raise students’ level of reading comprehension. Although our moderator analysis shows that motivation-only interventions do have a positive effect on reading comprehension, such interventions are often an addition to the existing reading curriculum. Naturally, growth in reading comprehension is a consequence of regular reading education as well, although motivational support appears to strengthen this effect.

The moderator effect of gender is promising, as especially boys are often characterized by low reading motivation (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Logan & Johnston, 2009; McKenna et al., 1995; Parson et al., 2018). Struggling readers also often have low reading motivation levels (McKenna et al., 1995; Toste et al., 2020; Vaknin-Nusbaum et al., 2018). The results of our meta-analysis indicate that reading motivation interventions are equally effective in fostering the reading motivation of struggling and typical readers. However, the effects of reading comprehension were smaller for struggling readers, suggesting that these students may need more instruction to improve their reading proficiency to the same extent as typical readers. Effects on reading comprehension were significantly larger for primary schoolers than for secondary schoolers; for the latter students, the effect was only marginal. This may be explained by the fact that students in primary education usually make larger gains in reading skills than students in secondary education (Bloom et al., 2008). Therefore, smaller effects may be expected in secondary education. However, conclusions for secondary schoolers remain somewhat tentative, as only a small share of the interventions (20%) focused on these students. More research is needed to get more insight into effective reading promotion in secondary education.

Three other moderators had significant effects: provider of the intervention, total intervention duration, and type of measurement. Interventions delivered by researchers had larger effects on reading comprehension than interventions delivered by others (in most cases teachers), possibly because researchers paid more attention to implementing the intervention with levels of high fidelity than teachers (c.f., Edmonds et al., 2009; Okkinga et al., 2018). This result underlines the importance of thoroughly communicating program principles to those who are conducting interventions in the field (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Effects on motivation were larger if the total duration of the intervention was longer, which indicates the importance of investing in students’ reading motivation during a longer period of time. The largest effects on reading motivation were found on teacher reports. However, it should be noted that teacher reports were only used in one study, so no strong conclusion can be drawn from this outcome.

Other moderators (text genre, study design, type of control group, and whether instruments were developed within the context of the study or not) showed no significant effects. The fact that positive effects were observed in studies with a strong design and on study-independent measures as well further substantiates our conclusions that reading motivation interventions can positively influence students’ reading motivation and reading comprehension.

Limitations and Future Research

When interpreting the results of this meta-analysis, some limitations should be considered. We examined the effects of theory-based motivational mechanisms on reading motivation and reading comprehension. In many interventions, a combination of these mechanisms was applied. The sample of studies in the meta-analysis was not large enough to test the effects of all combinations. Therefore, we tested whether interventions in which certain mechanisms were triggered had larger effects on reading motivation or reading comprehension than interventions in which these mechanisms were not triggered. Future studies may reveal whether certain combinations of motivational mechanisms are more effective than other combinations.

We aimed to identify which theoretical mechanisms contribute to the promotion of reading motivation and comprehension, thereby providing better insights into the effective ingredients of motivational interventions. Therefore, we only included theory-based interventions. Notwithstanding this strict inclusion criterion, we observed that, in several studies, the theoretical framework, the motivational mechanisms elicited, and the outcome variables did not always fully correspond. In future studies, researchers should thus be more precise in aligning the design of their interventions and the selection of measures with the theoretical model they choose to start from.

In conducting the moderator-analyses, we followed the analog-to-the-ANOVA procedure (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001), which is common practice in meta-analyses. However, some moderators likely overlap. For instance, interventions focusing on both motivation and skills instruction were often longer than interventions only focusing on motivation. Such confounding could be reduced by combining moderators in one analysis. However, such an analysis would require a larger set of studies than available in the present meta-analysis.

A limitation in many studies is that they did not examine treatment fidelity. Despite its importance in interpreting intervention effects (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), we found that slightly more than half of the studies reported on implementation. The moderator effect of provider of the intervention suggests that implementation quality was a factor in the interventions we examined. This outcome stresses the need for attention to monitoring program implementation in practice and research.

Conclusion and Implications

We conclude that there is an effect of motivational interventions on both reading motivation and reading comprehension. Our meta-analysis thereby contributes to the debate about the direction of the association between motivation and achievement (Aunola et al., 2002; Becker et al., 2010; Schiefele et al., 2016): our outcomes provide ground for the hypothesis that reading motivation affects reading proficiency, either independently or as part of a process of reciprocal causation. This, in turn, suggests that motivational support should be part of a model of reading instruction (Duke et al., 2011; Duke & Cartwright, 2021).

The results of our meta-analysis also provide information on what are the most effective ingredients of reading motivation interventions. Interventions that aimed to trigger students’ interest had the largest effects on reading motivation and reading comprehension. This outcome can inform teachers who are committed to furthering their students’ reading development, developers of educational methods, and those who make decisions about curricula for reading education. It seems particularly important to trigger students’ interest, for example, by matching texts to students’ reading levels or by making real-world connections.

At the same time, our meta-analysis provides an impetus for further research. We are in need of studies that examine whether positive effects are sustained over time. Furthermore, studies should take into account implementation quality and provide information on how to best support teachers in implementing motivational mechanisms. Finally, future studies should not only examine how to promote affirming motivations but also to decrease undermining motivations.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

*Aarnoutse, C., & Schellings, G. (2003). Learning reading strategies by triggering reading motivation. Educational Studies, 29(4), 387-409. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569032000159688

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261

*Andreassen, R., & Bråten, I. (2011). Implementation and effects of explicit reading comprehension instruction in fifth-grade classrooms. Learning and Instruction, 21(4), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.08.003

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Onatsu-Arvilommi, T., & Nurmi, J. E. (2002). Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and self-concept. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902320634447

Baker, L., & Wigfield, A. (1999). Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(4), 452–477. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.34.4.4

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

*Bates, C. C., D’Agostino, J. V., Gambrell, L., & Xu, M. (2016). Reading recovery: Exploring the effects on first-graders’ reading motivation and achievement. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 21(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2015.1110027

Becker, M., McElvany, N., & Kortenbruck, M. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 773–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020084

Bloom, H. W., Hill, C. J., Black, A. R., & Lipsey, M. W. (2008). Performance trajectories and performance gaps as achievement effect-size benchmarks for educational interventions. Methodological Studies, 1(4), 289–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345740802400072

*Bråten, I., Johansen, R., & Strømsø, I. (2017). Effects of different ways of introducing a reading task on intrinsic motivation and comprehension. Journal of Research in Reading, 40(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12053

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Rintamaa, M., & Carter, J. C. (2016). Supplemental reading strategy instruction for adolescents: A randomized trial and follow-up study. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.917258

*Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Rintamaa, M., Carter, J. C., Pennington, J., & Buckman, M. (2014). The impact of supplemental instruction on low-achieving adolescents’ reading engagement. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(1), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2012.753859

Conradi, K., Jang, B. G., & McKenna, M. C. (2014). Motivation terminology in reading research: A conceptual review. Educational Psychology Review, 26(1), 127–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9245-z

Cook, D. A., & Artino, A. R. (2016). Motivation to learn: An overview of contemporary theories. Medical Education, 50(10), 997–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13074

*Cuevas, J. A., Russell, R. L., & Irving, M. A. (2012). An examination of the effect of customized reading modules on diverse secondary students’ reading comprehension and motivation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(3), 445–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9244-7

De Naeghel, J., & Van Keer, H. (2013). The relation of student and class-level characteristics to primary school students’ autonomous reading motivation: A multi-level approach. Journal of Research in Reading, 36(4), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrir.12000

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progress: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Strachan, S. L., & Billman, A. K. (2011). Essential elements of fostering and teaching reading comprehension. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (pp. 51–93). International Reading Association.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669529

Edmonds, M. S., Vaughn, S., Wexler, J., Reutebuch, C., Cable, A., Tacket, K. K., & Schankenberg, J. W. (2009). A synthesis of reading interventions and effects on reading comprehension outcomes for older struggling readers. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 262–300. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325998

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3403_3

*Förster, N., & Souvignier, E. (2014). Learning progress assessment and goal setting: Effects on reading achievement, reading motivation, and reading self-concept. Learning and Instruction, 32, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.02.002

*Fowler, J. W., & Peterson, P. L. (1981). Increasing reading persistence and altering attributional style of learned helpless children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73(2), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.2.251

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfired, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.93.1.3

Guthrie, J. T., & Coddington, C. S. (2009). Reading motivation. In K. R. Wenzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 503–525). Routledge.

Guthrie, J. T., Coddington, C. S., & Wigfield, A. (2009). Profiles of reading motivation among African American and Caucasian students. Journal of Literacy Research, 41(3), 317–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862960903129196

Guthrie, J. T., Hoa, A. L. W., Wigfield, A., Tonks, S. M., Humenick, N. M., & Littles, E. (2007). Reading motivation and reading comprehension growth in the later elementary years. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(3), 282–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.004

Guthrie, J. T., & Klauda, S. L. (2014). Effects of classroom practices on reading comprehension, engagement, and motivations for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(4), 387–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.81

Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.035

Guthrie, J. T., McRae, A., & Klauda, S. L. (2007). Contributions of concept-oriented reading instruction to knowledge about interventions for motivation in reading. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 237–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701621087

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (1999). How motivation fits into a science of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0303_1

*Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Davis, M. H., Scafiddi, N. T., & Tonks, S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.3.403

*Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & VonSecker, C. (2000). Effects of integrated instruction on motivation and strategy use in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 331-341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.331

*Hautula, J., Ronimus, M., & Junttila, E. (2022). Readers’ theater projects for special education: A randomized controlled study. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2042846

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Ho, A. N., & Guthrie, J. T. (2013). Patterns of association among multiple motivations and aspects of achievement in reading. Reading Psychology, 34(2), 101–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2011.596255

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S. L., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73(2), 59–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00421

*Kao, G. Y., Tsai, C., Liu, C., & Yang, C. (2016). The effects of high/low interactive electronic storybooks on elementary school students’ reading motivation, story comprehension and chromatic concepts. Computers & Education, 100, 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.013

*Kim, J. S., Burkhauser, M. A., Mesite, L. M., Asher, C. A., Relya, J. E., Fitzgerald, J., & Elmore, J. (2020). Improving reading comprehension, science domain knowledge, and reading engagement through a first-grade content literacy intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000465

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4752(01)00011-1

*Kurnaz, A., Arslantas, S., & Pursun, T. (2020). Investigation of the effectiveness of personalized book advice smart application on secondary school students’ reading motivation. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 6(3), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.6.3.587

*Law, Y. (2011). The effects of cooperative learning on enhancing Hong Kong fifth graders’ achievement goals, autonomous motivation, and reading proficiency. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(4), 402–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01445.x

*Lee, Y. (2014). Promise for enhancing children’s reading attitudes through peer reading: A mixed method approach. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(6), 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.836469

Lepper, C., Stang, J., & McElvany, N. (2021). Gender differences in text-based interest: Text characteristics as underlying variables. Reading Research Quarterly, 57(2), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.420

*Levinson, E. M., Vogt, M., Barker, W. F., Jalongo, M. R., & Van Zandt, P. (2017). Effects of reading with adult tutor/therapy dog teams on elementary students’ reading achievement and attitudes. Society & Animals, 25(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341427

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Pekrun, R. (2016). Adaptive motivation and emotion in education: Research and principles for instructional design. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216644450

Lipsey, M. W. (2003). Those confounded moderators in meta-analysis: Good, bad, and ugly. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716202250791

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (1993). The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: Confirmation from meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 48(12), 1181–1209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.12.1181

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Sage.

Logan, S., & Johnston, R. (2009). Gender differences in reading ability and attitude: Examining where these differences lie. Journal of Research in Reading, 32(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.01389.x

Margolis, H., & McCabe, P. P. (2003). Self-efficacy: A key to improving the motivation of struggling readers. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 47(4), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880309603362

*Marinak, B. A., (2013). Courageous reading instruction: The effects of an elementary motivation intervention. The Journal of Educational Research, 106(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2012.658455

*Marinak, B. A., & Gambrell, L. B. (2008). Intrinsic motivation and rewards: What sustains young children’s engagement with text? Literacy Research and Instruction, 47(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070701749546

McBreen, M., & Savage, R. (2020). The impact of motivational reading instruction on the reading achievement and motivation of students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09584-4

McGeown, S., Bonsall, J., Andries, V., Howarth, D., & Wilkinson, K. (2020). Understanding reading motivation across different text types: Qualitative insights from children. Journal of Research in Reading, 43(4), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12320

McKenna, M. C., Conradi, K., Lawrence, C., Jang, B. G., & Meyer, J. P. (2012). Reading attitudes of middle school students: Results of a U. S. survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(3), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.021

McKenna, M. C., Kear, D. J., & Ellsworth, R. A. (1995). Children’s attitudes toward reading: A national survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 30(4), 934–956. https://doi.org/10.2307/748205

Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 37(2), 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021890

*Monteiro, V. (2013). Promoting reading motivation by reading together. Reading Psychology, 34(4), 301–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2011.635333

Morgan, P. L., & Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Exceptional Children, 73(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290707300203

Murphy, P. K., & Alexander, P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 3–53. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1019

*Nevo, E., & Vaknin-Nusbaum, V. (2020). Enhancing motivation to read and reading abilities in first grade. Educational Psychology, 40(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1635680

*Ng, C. C., Bartlett, B., Chester, I., & Kersland, S. (2013). Improving reading performance for economically disadvantaged students: Combining strategy instruction and motivational support. Reading Psychology, 34(3), 257–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2011.632071

Nielen, T. M. J., Mol, S. E., Sikkema-De Jong, M. T., & Bus, A. G. (2016). Attentional bias toward reading in reluctant readers. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.11.004

Niemic, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Nippold, M. A., Duthie, J. K., & Larsen, J. (2005). Literacy as a leisure activity: Free-time preferences of older children and young adolescents. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2005/009)

Nolen, S. B. (2007). Young children’s motivation to read and write: Development in social contexts. Cognition and Instruction, 25(2), 219–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370000701301174

OECD. (2019a). PISA 2018 results (Volume I): What students know and can do. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 results (Volume II): Where all students can succeed, PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/19963777

Okkinga, M., Van Steensel, R., Van Gelderen, A. J. S., Van Schooten, E., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Arends, L. R. (2018). Effectiveness of reading-strategy interventions in whole classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(4), 1215–1239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9445-7

Parsons, A. W., Parsons, S. A., Malloy, J. A., Marinak, B. A., Reutzel, D. R., Applegate, M. D., Applegate, A. J., Fawson, P. C., & Gambrell, L. B. (2018). Upper elementary students’ motivation to read fiction and nonfiction. The Elementary School Journal, 118(3), 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/696022

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). An achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1017

Reschly, A. L. (2010). Reading and school completion: Critical connections and Matthew effects. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 26(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560903397023

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

*Schaffner, E., & Schiefele, U. (2007). The effect of experimental manipulation of student motivation on the situational representation of text. Learning and Instruction, 17(6), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.015

Schaffner, E., Schiefele, U., & Ulferts, H. (2013). Reading amount as a mediator of the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.52

Schiefele, U. (1991). Interest, learning, and motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26(3-4), 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653136

Schiefele, U. (1999). Interest and learning from text. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0303_4

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.030

Schiefele, U., Stutz, F., & Schaffner, E. (2016). Longitudinal relations between reading motivation and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.031

*Schunk, D. H., & Rice, J. M. (1991). Learning goals and progress feedback during reading comprehension instruction. Journal of Reading Behavior, 23(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862969109547746

*Shelton, T., Anastopoulos, A. D. & Linden, J. D. (1985). An attribution training study with learning disabled children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 18(5), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221948501800503

Snow, C. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. RAND.

*Souvignier, E., & Mokhlesgerami, J. (2006). Using self-regulation as a framework for implementing strategy instruction to foster reading comprehension. Learning and Instruction, 16(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.12.006

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.21.4.1

Stefanou, C. R., Perencevich, K. C., DiCintio, M., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_2

Strommen, L. T., & Mates, B. F. (2004). Learning to love reading: Interviews with older children and teens. International Reading Association, 48(3), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.48.3.1

Stutz, F., Schaffner, E., & Schiefele, U. (2016). Relations among reading motivation, reading amount, and reading comprehension in the early elementary years. Learning and Individual Differences, 45(1), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.022

*Taboada Barber, A., & Buehl, M. M. (2013). Relations among Grade 4 students’ perceptions of autonomy, engagement in science, and reading motivation. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.630045

*Taboada Barber, A., Buehl, M. M., Beck J. S., Ramirez, E. M., Gallagher, M., Richey Nuland, L. N., & Archer, C. J. (2018). Literacy in social studies: The influence of cognitive and motivational practices on the reading comprehension of English learners and non-English learners. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34(1), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2017.1344942

*Taboada Barber, A., Buehl, M. M., Kidd, J. K., Sturtevant, E. G., Richey Nuland, L., & Beck, J. (2015). Reading engagement in social studies: Exploring the role of a social studies literacy intervention on reading comprehension, reading self-efficacy, and engagement in middle school students with different language backgrounds. Reading Psychology, 36(1), 31–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2013.815140

*Thames, D. G., & Reeves, C. K. (1994). Poor readers’ attitudes: Effects of using interests and trade books in an integrated language arts approach. Reading Research and Instruction, 33(4), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388079409558162

Toland, J., & Boyle, C. (2008). Applying cognitive behavioural methods to retrain children’s attributions for success and failure in learning. School Psychology International, 29(3), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034308093674

*Toste, J. R., Capin, P., Vaughn, S., Roberts, G. J., & Kearns, D. M. (2017). Multisyllabic word-reading instruction with and without motivational beliefs training for struggling readers in the upper elementary grades: A pilot investigation. The Elementary School Journal, 117(4), 593–615. https://doi.org/10.1086/691684

*Toste, J. R., Capin, P., Williams, K. J., Cho, E., & Vaughn, S. (2019). Replication of an experimental study investigating the efficacy of a multisyllabic word reading intervention with and without motivational beliefs training for struggling readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 52(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219418775114

Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., & McClelland, A. M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relations between motivation and reading achievement for K-12 students. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 420–456. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320919352

Troyer, M., Kim, J. S., Hale, E., Wantchekon, K. A., & Armstrong, C. (2019). Relations among intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, reading amount, and comprehension: A conceputal replication. Reading and Writing, 32(5), 1197–1218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9907-9

*Turan, T., & Şeker, B. S. (2018). The effect of digital stories on fifth-grade students’ motivation. Journal of Education and Future, 13, 65–78.

Unrau, N. J., Rueda, R., Son, E., Planin, J. R., Lundeen, R. J., & Muraszewski, A. K. (2018). Can reading self-efficacy be modified? A meta-analysis of the impact of interventions on reading self-efficacy. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 167–204. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317743199

Vaknin-Nusbaum, V., Nevo, E., Brande, L., & Gambrell, L. (2018). Developmental aspects of reading motivation and reading achievement among second grade low achievers and typical readers. Journal of Research in Reading, 41(3), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12117

Van Steensel, R., Oostdam, R., & Van Gelderen, A. (2019). Affirming and undermining motivations for reading and associations with reading comprehension, age, and gender. Journal of Research in Reading, 43(3-4), 504–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12281

Van Yperen, N. W., Blaga, M., & Postmes, T. (2015). A meta-analysis of the impact of situationally induced achievement goals on task performance. Human Performance, 28(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1006772

*Villiger, C., Niggli, A., Wandeler, C., & Kutzelmann, S. (2012). Does family make a difference? Mid-term effects of a school/home-based intervention program to enhance reading motivation, Learning and Instruction, 22(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.07.001

Walker, B. J. (2003). The cultivation of student self-efficacy in reading and writing. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308217

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

Wigfield, A. (1997). Reading motivation: A domain-specific approach to motivation. Educational Psychologist, 32(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3202_1

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.420

*Wigfield, A., Guthrie, J. T., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Klauda, S. L., McRae, A., & Barbosa, P. (2008). Role of reading engagement in mediating effects of reading comprehension instruction on reading outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20307

*Wigfield, A., Guthrie, J. T., Tonks, S., & Perencevich, K. C. (2004). Children’s motivation for reading: Domain specificity and instructional influences. The Journal of Educational Research, 97(6), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.97.6.299-310

Wilson, D. B., & Lipsey, M. W. (2001). The role of method in treatment effectiveness research: Evidence from meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.413

*Wolters, C. A., Barnes, M. A., Kulesz, P. A., York, M., & Francis, D. J. (2017). Examining a motivational treatment and its impact on adolescents’ reading comprehension and fluency. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(1), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1048503

*Wu, L., Valcke, M., & Van Keer, H. (2021). Supporting struggling readers at secondary school: An intervention of reading strategy instruction. Reading and Writing, 34(8), 2175–2201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10144-7

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wichor Bramer for his help with designing and conducting the literature search.

Funding

This work was supported by the Netherlands Initiative for Education Research (NRO; grant number 405-15-717).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author